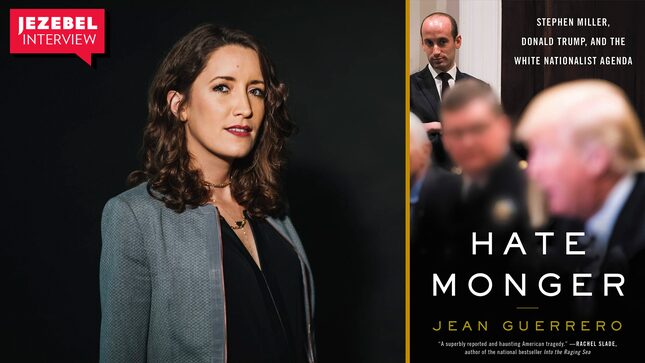

What Happens When a Racist Troll Runs National Policy? A Chat With Stephen Miller Biographer Jean Guerrero

Politics

Image: Array

Stephen Miller may appear like a grimacing extra on Sesame Street meant to prove a point about animus, but he is unquestionably the most toxic person in American politics, the warped draftsman of some of the most overtly racist policies in decades. Yet he has operated largely in the shadows, preferring to wield his power as the most extremist Trump advisor in an administration overflowing with extremists, emerging on occasion for news interviews in an attempt to warp public narrative and defend his white nationalist friends.

For the majority of reasonable Americans, the primary question around Miller has often been, simply, how and why: How did Stephen Miller, just 34, slither into amassing such power, and why did he become such a vile, anti-immigrant/anti-Muslim white nationalist in the first place? These are questions Hatemonger, journalist Jean Guerrero’s excellently reported new Miller biography, seeks to answer, following Miller’s radical indoctrination from his middle school years up to his current position in the White House. Guerrero, an investigative reporter who has covered immigration and the border for more than a decade and wrote 2018’s acclaimed Crux: A Crossborder Memoir, sought to uncover the way a person with Miller’s background—the descendant of Jewish pogrom refugees who grew up in relatively liberal Santa Monica, California—could become an almost cartoonish avatar for the brand of hatred his ancestors had to flee. In her extensively researched journey through Miller’s trajectory, she finds that the answer is all too banal and increasingly common—an angry young white man, enraged by the perceived threat posed by people of color and women gaining the tiniest iota of power, gets on the internet and decides to do something about it.

While Hatemonger has been framed as a typical Washington insider exposé, it’s far from just another Trump-era bio compiled mathematically by the usual suspects on the Hill. Guerrero, a Latina of Mexican and Puerto Rican descent who grew up in California at the same time as Miller, brings a too-rare understanding of the cultural context in which a person like Miller can thrive. Her book begins with the virulently anti-immigrant Proposition 187—the 1994 California ballot initiative that foreshadowed the current White House’s draconian aspirations for immigration “reform”—and traces the way the hatred coalesced into policy has been stoked for nearly 30 years; in doing so, she provides a deeper look into how a person so diametrically opposite to the values America claims to hold dear was able to rise to the White House in the first place.

Jezebel spoke with Guerrero over the phone last week about Hatemonger, internet radicalization, “cancel culture,” antifa, and Trump’s narrative of “protecting” white women. This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

JEZEBEL: My first question is—why did you do this to yourself? By which I mean, your book is excellently written and reported, but it seems like a tedious undertaking simply by rights of who Stephen Miller is. How did you decide that this was the next book you wanted to do?

JEAN GUERRERO: I’ve always been drawn to stories of strange, kind of outsider characters. Stephen Miller is now at the seat of power and is not a fringe person at all, but he was, kind of, throughout his life. I was drawn to him because of his outsider status, having grown up in what is considered to be a progressive town, within a diverse environment and progressive public high school, but having expressed conservative views throughout his life. Even when he was first on Capitol Hill, when the Republican Party was really moving towards immigration reform and a more moderate line and compromising with the Democrats—he was really pushing it in the opposite direction. His extremism was really fascinating to me.

And secondly, I’ve been covering immigration since the Obama Administration, but I really started to become more interested in the story of Stephen Miller while I was covering family separations. I was on the ground at the biggest border crossing in the country and interviewing all these parents who were getting separated from their kids. One case, in particular, was a father named José from El Salvador, with a one-year-old, Mateo, who hadn’t broken any laws. He’d presented his case legally at the port of entry, asked for asylum, had no criminal record—and was separated. And I was listening to the White House— Kirstjen Nielsen and Trump—saying that family separations are about law and order, they’re about national security. But I was on the ground and I knew that that wasn’t the case, because they were separating a bunch of families who had done everything the legal way.

So that, for me, raised the question: If this isn’t about law-and-order, if this isn’t about national security, then what is it about? I wanted to understand the motivations of the man who is crafting these policies. And the more I learned about him—like realizing that he is a descendant of refugees who also grew up in Southern California at the same time that I did in the ‘90s—that got me all the more intrigued. I wanted to answer the question, how does a Jewish American descendent of refugees, who’s crafting Trump’s harshest rhetoric and policies, target people fleeing violence and persecution, just like his grandparents?

Do you think that you found that answer? What can make a person so heartless?

I mean, that is kind of like the most important question, right? Like, how does this happen? And for me, I guess it’s a complicated answer, but it kind of boils down to this idea of radicalization and indoctrination during a difficult during a vulnerable period in your life. From my conversations with his family and with his friends and classmates, Miller developed relationships with these really radical right-wingers during a time in his life that was full of turmoil, in which he was looking for somebody to blame. It’s interesting because it’s like a microcosm for what was happening overall in the state of California at the time when I was growing up—at the time, Governor Pete Wilson was blaming all of the state’s problems on the migrant “invasion,” is what he called it.

Everybody was attacking affirmative action and bilingual education and social services for migrants—migrants were really the scapegoat statewide.

Stephen Miller grew up in that environment and was listening to Rush Limbaugh and Larry Elder and exposed to these ideas. He was going through a very difficult period in his life with his dad getting involved in all these legal disputes, and the family had to move to a less affluent part of town. I think he was looking for somebody to blame. It started out with him just acting out to try to get his father’s attention, is what I gathered from my conversations with people. And then he began to realize that this was a way of getting attention on a broader scale. It really gave him a sense of power and a sense of control that he didn’t have before; it started out as getting his dad’s attention, and then it became a core part of his identity. It almost seems like it supplanted his identity, really. Because during my early conversations, people [said they didn’t] really know if Stephen Miller was joking.

STEPHEN MILLER SOUNDS THE SAME TODAY AS HE DID WHEN HE WAS 16. IT’S THE SAME TOPICS, THE SAME INCENDIARY LANGUAGE, AND IT JUST NEVER WENT AWAY FOR HIM.

But over time, as he became more radicalized with figures like David Horowitz, who really drilled into him the idea that America is in danger and that liberals pose a literal existential threat, because of their allyship with “enemies” who want to bring America down—all of whom happen to be people of color. I feel like it eventually becomes very serious for Stephen Miller, and he starts to lose touch with the more lighthearted aspects of who he used to be. He becomes very mission-driven and obsessed with this idea that he’s saving America—like, literally. I truly believe that Stephen Miller, at least to some extent, and much more than Donald Trump, truly believes the things that he says. And he thinks that he is on a mission to save the United States from, you know, Muslims and immigrants from Mexico.

So, really basic psychology. I want to take it back to Prop 187, the 1994 ballot initiative that resulted from this race-baiting immigrant panic in California. The way you framed your book with Prop 187 as your starting point was excellent, because, in the broader context, Prop 187 was a political turning point that led to where we are now. And from a personal standpoint, I related to it because, like you, I was a Mexican American teenager when it was introduced, and Prop 187 really helped radicalize me—in the opposite direction, obviously, from Miller. [Sad Laughs]

I feel like that is what ended up happening—that is why California is now the state that it is, the way that it provoked a huge backlash from people who realized the way that the Republican Party was organizing the entire state against Mexicans and other Latinos.

I approached writing the Stephen Miller book with a completely open mind, thinking well, maybe this guy has been completely misunderstood. And there was a part of me that sympathized with the young Stephen Miller, who internalized all of the racism and white supremacy that he was exposed to growing up, because I remember growing up in that environment. I remember there was a sense of shame associated with being Mexican American because it had so deeply seeped into the culture. People like my family, like many other families in the state, wanted to hide the fact that we were Mexican. My mom’s Puerto Rican, but she used to always tell me like, you are American, you are not Mexican. And so for me, I can hear echoes of that in Stephen Miller’s early writings and rhetoric. It made me feel a level of sympathy for him because I remember that feeling of wanting to be perceived as American with all of the rights that being American is supposed to guarantee. You know, like just feeling a sense of shame associated with being Other—like, my dad used to wash my hair with chamomile shampoo, hoping that my hair would stay blond. There’s just this obsession with what it means to be “American.” And so that was one thing that was really interesting to me to explore with Stephen Miller—how he internalized that as a Jewish American boy.

He has writings where he talks about like, you know, Jewish people are the minorities, so Jewish holidays are not as important to him as American holidays. That, to me, was really interesting to just try to understand why? But for him, it never changed, because Stephen Miller sounds the same today as he did when he was 16. If you compare his writings, if you compare his rhetoric, it’s the same topics, the same incendiary language, and it just never went away for him.

But yeah, for me growing up in that environment, it gave me a level of like, OK, I’m not going to approach Stephen Miller with complete hostility when I started this reporting project. I understand what it’s like to grow up in that environment of wanting to be seen as belonging and sort of internalizing that white supremacy, but then trying to understand: How did he never come out of that? And that’s where the radicalization comes in.

I remember Prop 187 and people using the insults that I referred to in the book, you know, “beaner” and stuff like that. It really changed over the course of the early 2000s, but there was a point where there were a lot of Mexican American and Hispanic families, and I think just any families of color, who were really internalizing that rhetoric.

You’re making me choke up a little bit because I think there is a generation or two of Mexican immigrants that really did internalize this idea that no, we are American first because of all these myths that America told itself, and that erasure is destructive.

I remember the words that my mom used to say—and I don’t view them with any sort of judgment because I understand that she had faced so much discrimination as a physician with a Puerto Rican accent—like she just wanted me to feel that I belonged and to be treated as belonging by the greater community. But in retrospect, I see how destructive it is to associate Americanness and being a part of America with, like, self-loathing and rejecting your roots and annihilating your history, which I think is really what Stephen Miller was pushing at Santa Monica High School. Throughout his adolescence—at least with Larry Elder, one of his first mentors, who is a Black man—he was able to get along with people of color, so long as they renounced and rejected their unique ethnic history and roots and considered themselves to be American, period. And over time, you realize how destructive that can be.

I wonder if you can speak to the way Miller sanitizes these often white supremacist philosophies into catchphrases—like the whole “cancel culture” trope reeks of “political correctness” and “campus censorship,” which Miller was essentially decrying in in 2004. This is now coming up even with people who are so-called liberals as some sort of firebrand talking point.

The cancel culture thing is a perfect example, and like you see Stephen Miller really using this term lately—like he actually said during a recent interview with the podcast on The Washington Examiner, that cancel culture is the gravest threat facing America today, and that the federal forces being sent to Democrat-run cities is an effort to combat cancel culture. But it’s just lumping anyone who criticizes white supremacy into this category that purposefully inverts the morality of fighting white supremacy. It’s something that he learned from Horowitz, like completely inverting the arguments of the Civil Rights Movement to use against people of color, like calling people of color racists or calling liberals oppressors.

But your question was about his scrubbing of language.

HE’S LAUNDERING WHITE NATIONALIST TALKING POINTS THROUGH THE LANGUAGE OF HERITAGE, ECONOMICS, AND NATIONAL SECURITY

Yeah, I’m sure he learned so much of this from Limbaugh, but the coining of catchphrases that people can glom onto without having to think about what they really mean.

The use of catchphrases—Trump is so good at that. I think that one of the reasons Stephen Miller is so good at pointing out and weaponizing the hypocrisy of the left against them is because he grew up experiencing this, so he’s able to point out selective outrage when he sees it. Because you do see a lot of people being very angry about what is happening at the border under Trump who were kind of quiet about the unprecedented crackdown, through deportations, that the Obama Administration was doing. And so those kinds of double standards and hypocrisies, Stephen Miller is very skilled at weaponizing them and plucking them out, and it resonates with Trump voters who see it themselves. It’s one of the skills that Stephen Miller has because of the fact that he grew up in a progressive community.

But I think the most dangerous thing is dismissed—that he’s laundering white nationalist talking points through the language of heritage, and through the language of economics and the language of national security. That’s an extremely effective strategy. It allows people to believe that they’re supporting systematically cruel immigration policies because it’s in the national security interest or it’s in the interest of America’s prosperity. But when you actually connect the dots between what he’s doing and where it comes from, which is part of what I tried to do in the book, you realize like these are white nationalist talking points and what nationalist policy goals that he is laundering through this other rhetoric. It goes back to John Tanton creating these “think tanks” like Center for Immigration Studies (CIS) and the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR)—all these “think tanks” that Stephen Miller cultivates really close relationships with over the course of his life, which were essentially created, when you look at who John Tanton was and what his actual goals were, to make white supremacy palatable to the mainstream through these very banal-seeming, quote-unquote, “think tanks.”

That’s a skill that Stephen Miller brought to the Trump campaign—being very bookish and being able to immerse himself in in the research that was being produced by these groups that had been created by a eugenicist who believe in population control for nonwhite people and really believed in race-based pseudoscience and the genetic superiority of whites. He immersed himself in the research in order to insert it into the rhetoric and the policies of Trump.

FAIR issued a blueprint for Trump’s transition team in November of 2016 for immigration policy, and Stephen Miller’s immigration policy echoes that blueprint almost verbatim. The only thing that he hasn’t done that was requested by FAIR is the ending of birthright citizenship, and so I think that that’s one thing that’s probably coming. At least, I mean, they brought it up, and so they’re probably going to try.

As you’re talking about this, I’m thinking about the reframing of “antifa,” and how the Trump Administration is villainizing anti-fascism. Given everything you know about Stephen Miller from writing this book, where do you see this road leading?

To your antifa point, I don’t know if you ever were able to sit through Camp of the Saints, that super-racist book by Jean Respail?

No, please tell me.

Well, I initially skimmed it, because it was so painful, so disturbing to read. But I forced myself to really, really read it. And in my book, I talk about the way that it demonizes and dehumanizes people of color. But one of the other important, central components of that book is the way that it demonizes and dehumanizes the allies of people of color, and specifically names anti-racists as culpable for the destruction of the white world because of their allyship with people of color. And it echoes David Horowitz, but David Horowitz tries to whitewash that by not specifically calling out people of color, at least that’s my point of view.

If you read that book, it’s the exact same language that Trump is using now. It refers to anti-racist as anarchists and agitators who want to destroy Western Civilization—it used the exact same terms that Trump is using now, and I think we’re going to see a lot more of that.

It’s just scary to think how this extremely racist, white genocide book is seemingly being used by Stephen Miller as a playbook for Trump’s reelection strategy as far as the rhetoric and demonizing and any people who protest white supremacy as like people who are against the United States, which is just this is such a crazy idea to conflate. Like, you’re anti-American if you protest white supremacy, but he’s somehow able to sell it as not that, because he’s laundering it through that other language of national security and economics.

It’s just scary to think how this extremely racist, white genocide book is seemingly being used by Stephen Miller as a playbook for Trump’s reelection strategy

But as far as what the future holds—the optimistic side of me really does want to say that I think that the United States is currently going through the growing pains that California went through in the ‘90s, when white people became a minority in California for the first time. And that triggered all this fear and white rage and white backlash against people of color, because there was this idea that when whites became a minority, California would become like a third world state and civilization would fall apart—which is obviously not what happened. And we’re heading into whites becoming a minority in the United States, and similarly, there’s this idea like, oh, my God, the world is going to end among white supremacists.

But what’s going to happen is, we’re just going to become increasingly a mixed country. Black and brown people do not pose a threat to white people the way that white supremacists say they do, and it’s not as though they possess some superior virtue where they would never have the capacity to be oppressive in the same way that white people are. It’s just that we’re gonna become a more and more mixed society, where people have a greater capacity for identification with multiple groups. There’s gonna be less tribalism because there will be more and more hyphenated identities and just people who identify as multiple things.

I really do believe that we’re just heading into that phase that California eventually went through, where now diversity is something that can be celebrated and people realize that it doesn’t pose a threat to anyone. We’re gonna become a mestizo nation. And it’s something that Stephen Miller has always feared because he has been taught to believe that multiculturalism creates these inherent divisions in society where people hate each other. But that’s just because he was radicalized at a young age to believe that. In reality that’s not what happens—unless you’re fueling that!

I really appreciate your optimism, and on that note I want to ask you about Katie McHugh, a young woman who was radicalized by her time at Breitbart, but later realized she was being fed racist and sexist lies. You end your book with her, talking about the trauma of racist indoctrination. What struck you most about her transformation?

I think what struck me the most was how similar it was to Stephen Miller’s radicalization. Because when I trace things back with Stephen Miller, when he really started to get exposed to white supremacist ideas, the most concrete moment I can find is 2002, when David Horowitz puts an American Renaissance article on his homepage that he was allowing Stephen Miller to be published on as well. American Renaissance put out misleading Black and brown crime statistics, painting people of color as innately more violent and dangerous than white people.

And that is what Katie was telling me—because Stephen Miller was sending her all these statistics and articles that painted Black and brown people as violent animals, she just became really scared and angry, and like she had to do something to stop these people. It just strikes me how similar the reaction that she had was to Stephen Miller. Because she was also very young, she was in her early 20s, and she was you know, she talks about not having much of a community outside of Stephen Miller and the people that she was working with at Breitbart. But yeah, for me, it’s similar how banal it is—like you’re just living a normal life and then you just start to field these articles, and they have this veneer of being intellectually solid. American Renaissance looks, aesthetically, like some kind of legit magazine that puts out research and statistics. But that’s the whole idea of the white supremacist movement, like just trying to mainstream their ideas by cloaking them in this veneer of being serious research and things legitimate.

And then it’s that whole turning point of how easy it is to become radicalized if you’re going through a hard time, if you feel lonely, if you feel like you don’t have much of a community, and then suddenly you’re being exposed to material that you think is valid, and you feel like you suddenly have a mission in life. I feel like Stephen Miller and Katie McHugh were going through a period in their lives when they just didn’t feel like there was much meaning in their lives. And suddenly they felt like there was a meaning that they could cling to, trying to save the United States from the Third World. But it was this fantasy that, for Katie, once she started to realize that it was associated with real violence and that people were dying, it started to like poke holes in that illusion. And for Stephen Miller, it appears that that has not happened.

This just reminded me of the narrative that Trump has espoused about “protecting” white women, which obviously is extremely rooted in sexist white supremacy and the history of the antebellum South. How does that square with your research into Miller? Particularly because it’s been very connected to the idea that, you know, “Mexicans are going to rape your white wife,” basically. Has Miller weaponized that idea, and has he enabled Trump to bring up those talking points?

Stephen Miller is just really great at inserting gory language about the alleged crimes of immigrants into Trump speeches to rile up that fear. There was one anecdote being put in the immigration policy plan that Trump put out in 2015, before Miller was even officially working for the campaign—he was doing free labor for Trump—and one of the things that he puts in the immigration policy is like the story of this white woman who is in her house, and this migrant comes in and crushes her eye socket with a hammer. It’s very gory, vivid language that he used deliberately to incite hostile emotions about migrants.

And one of the first things that he did in the White House is create an office that was dedicated to the daily demonization of migrants to push out press releases about their crimes—VOICE, is what it was called. But for me, it stems back to the notion of masculinity that Stephen Miller was exposed to—Stephen Miller’s really obsessed with John Wayne, and this association of masculinity with violence, and this impenetrability, almost. I quote from it a little bit in the prologue, but I just love Rebecca Solnit’s idea of the ideology of isolation and how if you boil down right-wing ideology to one tiny little nugget, it’s this idea that, like, everything is disconnected from everything else. For me, that’s like toxic notions of what it means to be a man—completely disconnected in a way that makes you contemptuous of anything that is connected. Anything that is not impenetrable becomes contemptuous. And it’s like, when you look at how the idea of protecting white women from people of color is like has permeated the narratives of white supremacy, for me it goes back to that toxic idea of masculinity and how Stephen Miller’s dad, as described to me by people who knew him, is so similar to Donald Trump.

It’s why Stephen Miller has such influence over Trump. He just he’s the only adviser that Trump has that always pushes him in the most aggressive, most cruel direction. And Trump loves that, because whenever he listens to an adviser who pushes him in a more moderate direction, he ends up getting pummeled by his base as weak. The idea of being weak is just intolerable to people like Trump or Miller. That’s why they get along, because they just have this idea of like being “killers,” and like you’ve got to be a killer to society to be valuable. It’s almost like a fetish that they have, I mean Stephen Miller’s obsession with MS-13 and the crimes of MS-13, to the point of describing them in vivid, caring detail. Because people like Stephen Miller and Trump have such a morbid fascination with violence, it becomes almost like a competition for them. I think it threatens their own instincts of being killers, and they feel like they have to fight right back, as harshly as possible.

Jean Guerrero’s Hatemonger: Stephen Miller, Donald Trump, and the White Nationalist Agenda, is out now from HarperCollins.